Iconic British Architecture in Sliema

Architectural gems inherited from the British dot the Sliema landscape. Even though nowadays big blocks of apartments have taken over the Sliema seafront, we still can find magestic remnants of our British past.

Architectural gems inherited from the British dot the Sliema landscape. Even though nowadays big blocks of apartments have taken over the Sliema seafront, we still can find magestic remnants of our British past.

When the British landed on Malta in 1800, they weren’t much interested in asserting their power through any architecture, at least not until later in 1814, when they added the colonnaded portico to Valletta’s Main Guard (guard house), nowadays being the Office of the Attorney General. With time, their interest in making a more permanent foothold in Malta grew, and as colonial trade and sea traffic increased, along with a growing navy, Malta became an important part of the British colonial fist.

Villa Bighi in Kalkara was transformed into a Naval Hospital in 1832 and St Vincent de Paule Hospital was constructed in Luqa during the 1880s. The Naval Bakery in Birgu, that catered for the British Mediterranean fleet and built in the 1840s, is truly an astounding piece of architecture. The love for British-built Neo-Classical porticoes was hugely popular, and copied in such beautiful buildings as the Dragonara Palace in St Julians, Villa Pescatore in St Paul’s Bay and other architecture from the era.

Undoubtedly, the most important location for the British was Sliema. Derived from ‘peace’, the name of Sliema belonged to a quiet fisherman’s village that over the years became popularised into a summer resort for the wealthy, as early villas and palazzos in the area indicated. Later the British changed various areas into a residential hub, mainly for the families of those who worked with the Navy and other British institutions.

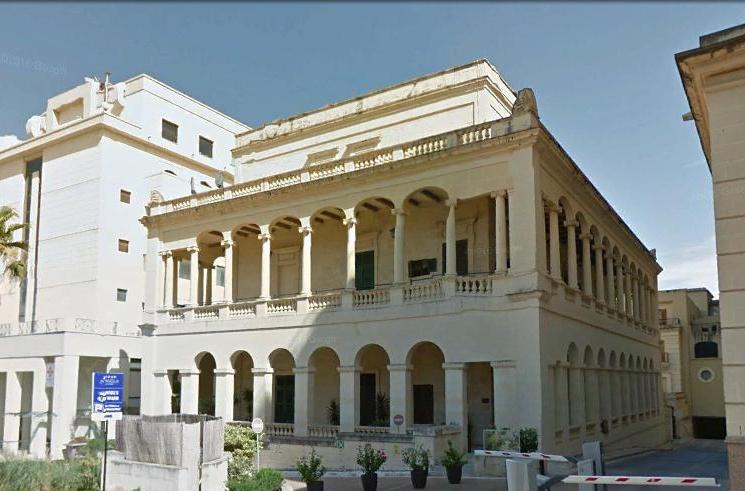

Within Sliema, nowadays serving as a private hospital, Capua Palace is one of the old, Neo-Classical buildings that encapsulates the architectural style for much of 19th-century British-built architecture. It was actually built by a Russian banker and only later came into the possession of the Prince of Capua, for whom the palace is still named today. Imagine this palace standing gloriously alone surrounded by a panorama of countryside and sea views.

It was around this palace that the wealthy Maltese (most of whom were well-to-do professionals from within The Three Cities, and the British built their palatial homes. For the Maltese, these were generally not their main residence but rather, a comfortable and luxurious summer residence. Nowadays Triq Gorg Borg Olivier has several remnants of this era—beautiful Neo-Classical and Neo-Baroque houses, notably the Villinu Twins.

The fusion of the Neo-Classical style with the local vernacular eventually bred an architecture that was to become a unique Maltese colonial style. Seen notably in the buildings in St Andrew’s where the British built a military complex, but also in Sliema. Its immediate neighbours Gzira and St Julians, inherited this eclectic architecture too.

Notably, one finds that the majestic Zammit Clapp Hospital in the limits of Sliema and its neighbour the Convent of the Sacred Heart are two fine examples of the Maltese colonial style at its best. A stone’s throw away, in St Julians, one finds the impressively enormous Balluta Buildings, an enigmatic building with its weird yet alluring mixture of styles —Art Nouveau, Neo-Gothic and Neo-Baroque—along with its size (possibly the largest building in Malta in its heyday). Other notable examples within Sliema can be discovered on walks around town, as this booming seaside hub is home to several, if dispersed, private homes from the British era.

The mystifyingly dilapidated Villa Drago up from Bisazza Street, that had views of Qui Si Sana and Ghar id-Dud bays, with a large garden to match; the column-porticoed homes in Annunciation Square, that still preserve a quaint reminder of Sliema village-life; and, close by, yet another dilapidated beauty in Triq Castelletti, a magnificent Victorian-era Neo-Classical building with a beautiful staircase and an enchanting colonnaded terrace.

Churches weren’t overlooked during this period, with two important examples in the Sliema area: the Holy Trinity Anglican Church in Rudolph Street (coincidentally standing right in front of the Moorish Terrace, a folly-house built by Emmanuele Galizia, the same architect who built the Turkish cemetery in Marsa); the Neo-Gothic Carmelite Church in Balluta Bay and Stella Maris Church.

All in all, Sliema basked during the passage of the British in more ways than one. The preservation of these iconic historical buildings ensures future generations will be able to appreciate this niche of very English architectural heritage on Malta.